Here we have the death-defying story of the laying of the Trans-Atlantic telegraph cable! Quite a monument for the technological achievement. Excerpt below:

The landing of the cable took place on Wednesday, the fifth of August, near the hour of sunset. As it was too late to proceed that evening, the ships remained at anchor till the morning. They got under weigh at an early hour, but were soon checked by an accident [Pg 132]which detained them another day. Before they had gone five miles, the heavy shore end of the cable caught in the machinery and parted. The Niagara put back, and the cable was “underrun” the whole distance. At length the end was lifted out of the water and spliced to the gigantic coil, and as it dropped safely to the bottom of the sea, the mighty ship began to stir. At first she moved very slowly, not more than two miles an hour, to avoid the danger of accident; but the feeling that they were at last away was itself a relief. The ships were all in sight, and so near that they could hear each other’s bells. The Niagara, as if knowing that she was bound for the land out of whose forests she came, bowed her head to the waves, as her prow was turned toward her native shores.

Slowly passed the hours of that day. But all went well, and the ships were moving out into the broad Atlantic. At length the sun went down in the west, and stars came out on the face of the deep. But no man slept. A thousand eyes were watching a great experiment as those who have a personal interest in the issue. All through that night, and through the anxious days and nights that followed, there was a feeling in every soul on board, as if some dear friend were at the turning-point of life or death, and they were watching beside him. There was a strange, unnatural silence in the ship. Men paced the deck with soft and muffled tread, speaking only in whispers, [Pg 133]as if a loud voice or a heavy footfall might snap the vital cord. So much had they grown to feel for the enterprise, that the cable seemed to them like a human creature, on whose fate they hung, as if it were to decide their own destiny.

There are some who will never forget that first night at sea. Perhaps the reaction from the excitement on shore made the impression the deeper. There are moments in life when every thing comes back upon us. What memories came up in those long night hours! How many on board that ship, as they stood on the deck and watched that mysterious cord disappearing in the darkness, thought of homes beyond the sea, of absent ones, of the distant and the dead!

But no musings turn them from the work in hand. There are vigilant eyes on deck. Mr. Bright, the engineer of the Company, is there, and Mr. Everett, Mr. De Sauty, the electrician, and Professor Morse. The paying-out machinery does its work, and though it makes a constant rumble in the ship, that dull, heavy sound is music to their ears, as it tells them that all is well. If one should drop to sleep, and wake up at night, he has only to hear the sound of “the old coffee-mill,” and his fears are relieved, and he goes to sleep again.

Saturday was a day of beautiful weather. The ships were getting farther away from land, and began to steam ahead at the rate of four and five miles an [Pg 134]hour. The cable was paid out at a speed a little faster than that of the ship, to allow for any inequalities of surface on the bottom of the sea. While it was thus going overboard, communication was kept up constantly with the land. Every moment the current was passing between ship and shore. The communication was as perfect as between Liverpool and London, or Boston and New York. Not only did the electricians telegraph back to Valentia the progress they were making, but the officers on board sent messages to their friends in America, to go out by the steamers from Liverpool. The heavens seemed to smile on them that day. The coils came up from below the deck without a kink, and unwinding themselves easily, passed over the stern into the sea. Once or twice an alarm was created by the cable being thrown off the wheels. This was owing to the sheaves not being wide enough and deep enough, and being filled with tar, which hardened in the air. This was a great defect of the machinery which was remedied in the later expeditions. Still it worked well, and so long as those terrible brakes kept off their iron gripe, it might work through to the end.

All day Sunday the same favoring fortune continued; and when the officers, who could be spared from the deck, met in the cabin, and Captain Hudson read the service, it was with subdued voices and grateful hearts they responded to the prayers to Him who [Pg 135]spreadeth out the heavens, and ruleth the raging of the sea.

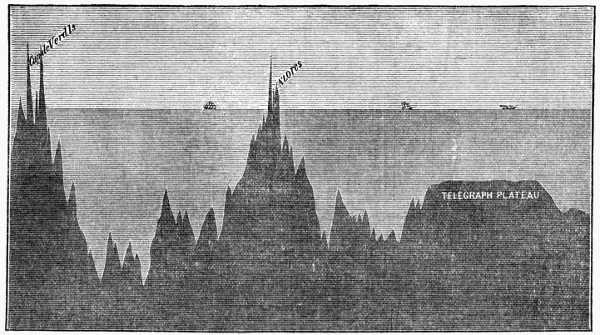

On Monday they were over two hundred miles at sea. They had got far beyond the shallow waters off the coast. They had passed over the submarine mountain which figures on the charts of Dayman and Berryman, and where Mr. Bright’s log gives a descent from five hundred and fifty to seventeen hundred and fifty fathoms within eight miles! Then they came to the deeper waters of the Atlantic, where the cable sank to the awful depth of two thousand fathoms. Still the iron cord buried itself in the waves, and every instant the flash of light in the darkened telegraph room told of the passage of the electric current.

But Monday evening, about nine o’clock, occurred a mysterious interruption, which staggered all on board. Suddenly the electrical continuity was lost. The cable was not broken, but it ceased to work. Here was a mystery. De Sauty tried it, and Professor Morse tried it. But neither could make it work. It seemed that all was over. The electricians gave it up, and the engineers were preparing to cut the cable, and to endeavor to wind it in, when suddenly the electricity came back again. This made the mystery greater than ever. It had been interrupted for two hours and a half. This was a phenomenon which has never been explained. Professor Morse was of opinion that the cable, in getting off the wheels, had been strained so [Pg 136]as to open the gutta-percha, and thus destroy the insulation. If this be the true explanation, it would seem that on reaching the bottom the seam had closed, and thus the continuity had been restored. But it was certainly an untoward incident, which “cast ominous conjecture on the whole success,” as it seemed to indicate that there were at the bottom of the sea causes which were wholly unknown and against which it was impossible to provide.

The return of the current was like life from the dead. Says Mullaly:

“The glad news was soon circulated throughout the ship, and all felt as if they had a new life. A rough, weather-beaten old sailor, who had assisted in coiling many a long mile of it on board the Niagara, and who was among the first to run to the telegraph office to have the news confirmed, said he would have given fifty dollars out of his pay to have saved that cable. ‘I have watched nearly every mile of it,’ he added, ‘as it came over the side, and I would have given fifty dollars, poor as I am, to have saved it, although I don’t expect to make any thing by it when it is laid down.’ In his own simple way he expressed the feelings of every one on board, for all are as much interested in the success of the enterprise as the largest shareholder in the Company. They talked of the cable as they would of a pet child, and never was child treated with deeper solicitude than that with which the cable is watched by them. You could see the tears standing in the eyes of some as they almost cried for joy, and told their messmates that it was all right.”